![]()

|

CONNECTING WITH TWEEN READERS

WELCOME STUDENTS OF ED SULLIVAN

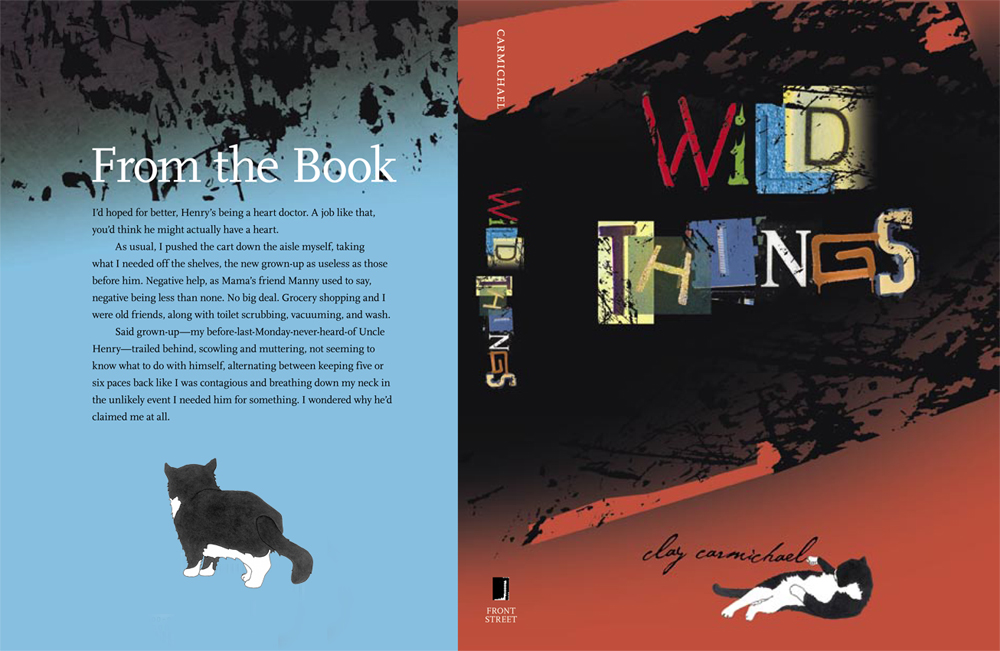

Q: Tell a bit about the challenges of writing fiction for Tween readers. A: The challenges are more or less the same as the challenges of writing fiction for any age: I strive to write a compelling story, characters that leap off the page and, though revision, to create emotional depth and resonance. I do find writing for young people demands greater clarity and precision in the language, simply because young people don't have the vocabulary of older readers, but those demands have made me a much better writer for all ages. Other than that, I'm not really thinking about my readers as I write. My first allegiance is to my story and my characters, to render them truly. So if I'm writing a cat, I need to live in the skin of a cat and if I'm writing an eleven-year-old girl, I have to live in the skin of that girl. My goal is to make both as real and as believable as possible. I call on my experience and my imagination, both. If the writing's going well, at the end of each day it's a bit like coming out of a trance. Over time and with a lot of revision, the story and characters deepen and the resonance comes, at least I hope so. Q: What has been the reader response? A: Really warm and wonderful. The publisher sells the book for "age 9 and up" but I'm finding 12 and up to be truer, and many adults are loving the story as well. Among Tweens, some relate more to the animals in the story and some to the girl. One Tween ran up to me at the North Carolina Literary Festival and said, "I am Zoë!" She made me write that in her book when I signed it. Q: What were your inspirations for writing Wild Things? A: For that, read the talk I gave at the 2009 North Carolina Literary Festival, below. |

|||

~Muses Are Everywhere~ |

|||

Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares. Hebrews 13:1-2

The first inspiration for my novel Wild Things walked into my life on all fours. I wish I could say that I took one look at that filthy, hungry, strikingly handsome creature and saw immediately the muse he was, knew instantly that he would steal my heart and transform my life. But ashamed as I am to admit it, I took one look at my four-footed muse and ran him right out of the yard. My muses have been non-standard from the start, when my father's Parkinson’s disease inspired me to write and illustrate my first picture book—and this was at a time when I not only didn’t illustrate, but hadn’t planned on authoring children’s books at all. Maybe other writers are better at knowing a muse when they see one, but looking back now at mine, I see a lot of unlikely angels entertained unawares. That dreary winter morning, I didn’t see any angel. I glanced out my Carrboro, North Carolina kitchen window and saw, crouched in the periwinkle under the bird feeder, an enormous black-and-white tomcat. His head was huge, a build-up of scar tissue from years of fighting, but I didn’t know that then. He was black except for a white chest, stomach, four white paws and a rough triangle of white around his muzzle that rose to a point between two green-gold eyes. To the right of his pink nose was his most distinguishing feature: an oval splotch of black, as though someone had stuck a thumb into black paint then pressed a solid, sideways thumbprint just there. His “half mustache” was as unmistakable as a tattoo, and gave him a goofy look. Goofy, except that his eyes were fixed on several sparrows and two brown rats feasting on fallen seeds. Goofy, except that he was poised to strike.

When I was a child growing up in Chapel Hill, my grandmother—a muse for both the grandmother and the intolerant churchwomen in Wild Things--watched her birds, as she called them, every afternoon at the kitchen window while she prayed the rosary. Though she’d become a Catholic after marrying my grandfather, her faith retained the pragmatic, reactionary character of her depression-era, Southern Baptist upbringing. Her feeders and statues of St. Francis welcomed some animals, but not others. She beheaded snakes with a hoe, bombed moles and voles in their tunnels, and poisoned chipmunks, mice and rats. She despised squirrels and fought her gray nemesis with greased poles, worthless baffles, idiotic-looking wire contrivances and relentless, unsuccessful craft. But though she hated squirrels, the antichrist would have been more welcome than a cat. So whenever I remember my grandmother perched on her step stool in afternoon prayer, I remember the cap pistol she kept on the counter beside her, and how at the sight of a squirrel or cat she left-fisted the rosary, right-handed the pistol and flew out the door firing and screeching, “Scat!”

I grew up to disagree with my grandmother that there were good animals and bad animals, that the pretty and well-behaved ones should be fed and the ugly or troublesome ones beheaded, poisoned or gassed. Everyone ate at the birdfeeder behind my Carrboro house, even squirrels and the occasional mouse or rat. The mice and rats came from a neighbor’s compost pile and the next-door open field, which belonged to my friend Ruby King, another muse, who I made a friend of my eleven-year-old main character, Zoë, in Wild Things. But even though I fed all kinds of animals in my backyard, I did think it was wrong to entice creatures to a feeder so that other animals could hunt them there, so I shooed away the hawks, snakes and cats—including my own tabby—when I caught them hunting underneath. Which was why, on that winter morning, I did something that I shall regret all my days. I imitated my grandmother, flew out the front door, raced to the side of the house and chased off that frightened, funny-faced cat. At the time the cat came, I was learning to write and illustrate picture books for children. My then-husband, Sam, and I called our house the Love Bungalow, because whatever it lacked in comfort, it was full of that good feeling. It didn't have insulation or reliable plumbing. It barely had heat. A big kerosene furnace took up most of the living room, but only heated the house to fifty or sixty degrees. On cold days, we could see our breath in the two upstairs rooms and I wore gloves when I drew or typed. There were cracks in the outside walls we could see the front yard through. We filled them, but they opened up again as the house settled, and it was always settling. A crack an inch or two wide ran through the living room floor and foundation; we called it the San Carrboro Fault. When it rained hard, the downstairs flooded. That house was surely my muse for the drafty forest log cabin my main character Zoë finds and fixes up in Wild Things. The winter the cat appeared the weather was unusually raw. Ice storms bowed the trees, and the wind cut more sharply into anything warm-blooded, doubling the number of hungry birds at the feeder. Now and then, I caught glimpses of the cat again from my upstairs study window, but he was always gone before I could run through the bedroom, down the backstairs, across the kitchen and outside to shoo him away—so I stopped bothering and began to watch him. His stark coloring made him stand out, as did the heavy way he walked, more like a lumbering lion than a house cat, though his stubby legs could sprint when they had to. He favored rats over poultry and unlike most cats, he never toyed with his prey before he killed it, which I admired. I remember vividly the day I understood that his hunting was a matter of life and death, that he was all alone in the world. I had just left my desk for lunch, and was walking by the bedroom window on the other side of the upstairs when I heard rustling in the leaves outside. I caught sight of him down below, hunched over something in the leaf litter. The area was overgrown with scraggly trees and privet; scattered with old tools, broken flowerpots, bricks and discarded clay pipe. He was tearing at something with his teeth and I saw he had killed a brown rat and was tearing off its fur in tufts to eat it, which he did, every edible bite. He ate quickly and ravenously, as the truly starving do. At first I felt sorry for the rat, then disgusted watching the cat eat it. But after a few minutes—which was all it took him to finish—I understood what I was really seeing: a lone, homeless, hungry animal surviving a hard winter as best he could. I realized he was wild.

These are the moments that I live for as an author. The moments in a character’s life where the heart shifts, where the eyes look and for the first time really see. That was the day my own heart shifted and I saw the cat’s life through his eyes. That was the day I began the first chapter of Wild Things, though it was years before I wrote a single word. In time, and it took a long time, that wild black-and-white cat came to trust me, and only me, the way the fictional cat in Wild Things comes to trust my main character Zoë, who has huge trust issues of her own. I, like Zoë, was patient, and, as in the book, one day that cat just decided about me. His cat heart shifted. He was sunning himself in the yard when I pulled into the drive. He was wary, as usual, as I got out of the car, but this time he didn’t bolt as I slowly approached him. Step by step I got closer, and closer still, and as I got to him he rolled over, showed me his belly and even let me scratch it. I have never felt so honored in my life. That was the beginning of our many years together and in those years we grew close. I called him Mr. C’mere, because "C’mere" was what he came to. During our time together, I wrote, illustrated and published three picture books. He made a cameo appearance in the third. He wasn’t ever tame. Until he was quite old, he went off for weeks at a time and came home as spent and bloody as a drunken sailor from doing what tomcats do best. His story and eventful life went on for ten more years, but it was the early years and our mutual shifts of heart that I tried to capture in Wild Things. Mr. C’mere and my first husband Sam died in the same year, within two months of each other. Mr. C’mere was very old, twenty the vet judged by his teeth. He died as peacefully as my husband did not. Loss is also a muse of Wild Things. The loss of love, of family, of home, of trust. At the beginning of Wild Things, the little girl Zoë has lost both her parents, along with any hope of a loving family, when her uncle Henry, a sculptor grieving the loss of his wife, takes her in. But Wild Things isn’t a tragic novel. In telling Zoë and the cat’s story, I wanted to write about what comes after the pain and the loss, about the restoration of trust. I wanted to write about human and animal resilience, those mutual shifts of heart; about the power of love to heal the heart and transform it. Which brings me to Wild Things’ other primary muse. One night, about three years after Sam and Mr. C’mere died, I was at a friends’ house admiring the beautiful stonework in their new outdoor pool, when I felt someone come up behind me, pick me up and dance me across the terrace. This someone was a sculptor, much like the sculptor I would later write about in Wild Things. He was someone I knew, though not well, but that changed pretty quickly. He and I were married six months later, and that was more than eight years ago. This muse I didn’t chase off, or have to work to win over. Sometimes muses take matters into their own hands. I don’t want to make too much of the “real life” in my book. My friend the storyteller Donna Washington says all her stories are true, except for the parts she makes up. I could name a dozen lesser muses. I could tell you, for instance, that the lifelike wooden animals the teen boy Wil carves in Wild Things were absolutely inspired by the beautiful wooden animal carvings of Carl Boettcher’s Circus Parade, a magnificent moving fixture of my childhood in Chapel Hill, first in the Circus Room of the old Monogram Club where we bought our ice cream cones when we were kids, then in the old Carolina Inn cafeteria where I ate hundreds of meals with my family, and last, now, in the UNC Alumni Center where I visit the Circus from time to time. But I also need to say that Wild Things is a work of fiction, a story I made up. Though my life and people and animals I know and have known inform the story, the situations and characters in it are really alive only in my imagination, and, I hope, in the pages of the book. In all creative work—at least all of mine—life and imagination converge. It’s my belief that all stories have happy endings depending on where you end them. I think I left Zoë and her cat in a promising place at the end of Wild Things. I live now very happily with my sculptor-husband in a beautiful sculpture-filled yard. Today, another mustachioed black-and-white cat from the shelter suns himself on the lawn. The house we live in, my muse Mrs. King’s former house, has heat and decent plumbing and stays warm and dry when it rains. But I can see the Love Bungalow, the drafty little house where I wrote my first book and met Mr. C’mere, from my studio window. And Mr. C’mere’s stone grave stands at the edge of the sculpture garden. Both are daily reminders, as Zoë observes in Wild Things, that things are beginning and ending, all in some measure, all the time—that muses are everywhere. Clay Carmichael September 12, 2009

|

|||

Additional reading about Wild Things & Clay Carmichael

Let's converse. Please email your questions and comments below. Thanks for your interest in my work. -Clay 2/1/10 |

|||

©2010 Clay Carmichael/All Rights Reserved |